UDI in America

9 August 2024

One of the conceits of the Harold Wilson government in Britain was to refer to the Rhodesian UDI (“Unilateral Declaration of Independence”) as IDI (“Illegal Declaration of Independence”). Later British governments similarly viewed Rhodesia and its government as illegal, but dropped the use of the novel acronym. Apparently, it had failed to catch on in the press.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence, too, was unilateral. And Britain likewise declared the newly independent American colonies to be “illegal.” Back then, Britain actually fought wars, even though its population in 1776 was only about one third of what it would be in 1965, and the only way to reach rebel colonies at the time was by wooden sailing ships. But fight America they did, twice.

The legality of U.S. independence was never resolved, by warfare or by any other means. In fact, we will soon be celebrating 250 years of glorious American “illegality.” The funny thing is, once you’re rich enough and powerful enough, no one cares.

Yet besides the fact that Rhodesia never became rich or powerful enough for anyone to overlook its unilateral origins, we somehow feel it was illegitimate in other ways as well. In particular, it was racist.

Britain never cited racism as a reason for fighting two wars against the United States. Was Rhodesia in 1965 more racist than America in 1776 and indeed than America over the following century or even two centuries? No one was ever enslaved in Rhodesia. As for lynchings, according to Robert Blake’s A History of Rhodesia:

Only two attempts are recorded — the earlier one in 1893 being stopped by Dr. Jameson with the characteristic and effective argument that Mashonaland was expecting a boom which would be wrecked if the world saw that it had no respect for law and order. He then stood drinks all around to the ring leaders.

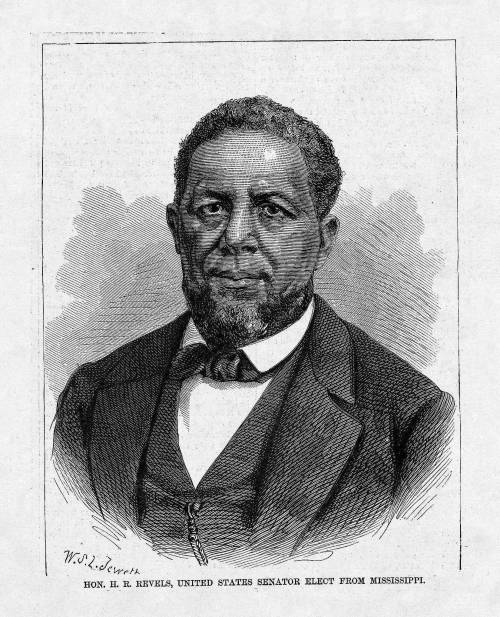

And yet here again, comparison with the United States is not so stark. All delegates to the Continental Congress were white and it is not clear if any black inhabitants of the colonies had any say in delegating them. No black man was elected to the U.S. congress until almost a century later, in1870. Nor is it clear if whites were a majority in America in 1776. The ancestors of most white people in America today didn’t arrive until long after independence while the ancestors of most black people in America today were already here before independence. Anyway, most people in North America at that time were Indians. And Indians living in the U.S. weren’t granted U.S. citizenship until President Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. Before that, Indians had to apply for U.S. citizenship on a case by case basis.

|

|

Another major source of suspicion and general ill-will towards Rhodesia was its qualified franchise. From its earliest constitution and the inception of self-government in 1923, anyone wishing to vote or stand for office in Rhodesia had to possess some kind of combination of education, wealth, or income. By 1961, these rights had been extended, regardless of wealth or income, to clergymen, chiefs, headman, and “all kraal heads with a following of twenty or more heads of families.”

There was formally no racial or gender discrimination in voting rights although few black people ever qualified. Single women could similarly qualify on their own merits, although it is hard to estimate how many actually did. Married women automatically had the same rights as their husbands. According to the 1961 constitution: “a married woman is deemed to have the same means qualifications as her husband. However, only the first wife under a system permitting of polygamy is deemed to have such qualifications.”

Beginning in 1961, a separate roll of voters was introduced whose means qualifications were lower and who elected a smaller number of representatives. The intent was to bring more blacks into the political system who would otherwise not qualify to vote, while at the same limiting the effect of their vote to less than that of the fully qualified voters. Aside from this later innovation, the Rhodesian system was actually fairly typical of Britain and its colonies. This included the American colonies, who retained such systems of franchise for many years after U.S. independence.

De Tocqueville summarizes voting requirements in the different U.S. states in Appendix H to Democracy in America. In New Jersey, only “freeholders,” i.e., people who held property free of mortgage, were allowed to vote or stand for office. The system eventually gave way to universal suffrage, but until 2020, county commissioners in New Jersey were still formally called “chosen freeholders.” Britain herself did not have universal male suffrage until the Representation of the People Act was passed in 1918.

And yet Rhodesia is still palpably different. It is different because it is so much smaller and began so much later.

Much breath and ink was wasted in endless negotiations between successive British governments and the Rhodesian Front between 1962 and 1968 hammering out the details of what the British would accept as a suitable independence constitution. Rube Goldberg devices involving multiple voter rolls, racially reserved seats, multiple chambers, and entrenched clauses were proposed and chewed over. Ian Smith stated several times during this period that his government was amenable to a number of the proposed constitutional models. The sticking point was always the British insistence on a “return to legality” as a final condition. This would include a “test” of any proposed new constitution, essentially a referendum under universal suffrage, to be administered by the British. The British would then decide whether to grant Rhodesia independence or else to appoint it a new government of its own choosing. It was never clear if even passing such a test would be a sufficient or only a necessary condition for independence. It all meant not only de facto universal suffrage, but surrender to direct British rule. Thus none of the constitutional models really mattered at all and the negotiations eventually came to be seen as a distraction and a scam.

As indeed they were. The British were under heavy pressure from the U.N., the Organization of African Unity, and the British Commonwealth whose majority was now African. Any settlement that would have allowed Rhodesia to continue to exist would have caused diplomatic problems that Britain was unwilling to face.

Other countries had had hundreds of years to sort these kinds of issues out. Furthermore, they did this without other countries or international bodies telling them how to do it. By the time independence became an issue in Rhodesia, Rhodesian self-government had been in existence a mere forty years and the British weren’t prepared to give the Rhodesian government any more time.

Consider that slavery didn’t end in the U.S. until four score and seven years after independence and Jim Crow segregation didn’t end until an additional 100 years after that. The Civil Rights Act wasn’t passed until 1964. No one at that time, except a very lonely Malcom X, was trying to get the United Nations and other countries involved. Rhodesia was being embargoed in 1965 for civil rights conditions that were hardly worse than those of Jim Crow that were only then ending in the U.S. The University of Rhodesia was desegregated from the time of its founding in 1952, ten years before James Meredith enrolled at Ole Miss.

None of this was lost on Rhodesians at the time, as is apparent in the following exchange between Ian Smith and Harold Wilson in the lead-up to UDI, as reported by Kenneth Young:

Smith observed that the Europeans had been in North America at least six times as long as they had been in Rhodesia. The standard of African education in Rhodesia was higher than in other African countries. All the same, Wilson replied, the British Government had felt justified in granting independence to those other African countries. True, replied Smith, and the consequences spoke for themselves. Tanzania, for example, was little more now than a Chinese puppet. Wilson did not deny nor affirm it.

Wilson then appeared to allow his temper to get the better of him and said that the Rhodesian Government’s attitude seemed to raise the same issues as those which had just been fought out in Alabama. Smith immediately pointed out that there were greater differences between European and African standards in Rhodesia than in the United States. If so, retorted Wilson, this might be a reflection on the extent to which Rhodesian Government had provided facilities for African education.

“This is not the fault of the law: the negroes have an undisputed right of voting, but they voluntarily abstain from making their appearance.”

“A very pretty piece of modesty on their parts!” rejoined I.

“Why, the truth is, that they are not disinclined to vote, but they are afraid of being maltreated; in this country the law is sometimes unable to maintain its authority without the support of the majority. But in this case the majority entertains very strong prejudices against the blacks, and the magistrates are unable to protect them in the exercise of their legal privileges.”

“How comes it, then, that at the polling-booth this morning I did not perceive a single negro in the whole meeting?”

People do not appreciate today how much the U.S. Constitution did to speed the end of slavery. It was written to govern a country in which slavery would not exist and its adoption led to the growth of a country in which slavery would become unworkable. The famous “three fifths compromise” meant that slave states could not fully count their enslaved populations for purposes of congressional and electoral representation. This effectively diluted the voting power of slave states. It is perverse that so many ignorant Americans today believe it was some sort of racist trick to devalue the human worth of black people or something like that.

From a legal point of view, slavery in America did not have a racial component. There was no racial restriction on who could become a slave nor was there any requirement that anyone of any particular race had to be enslaved. In fact, no free man of any race was ever made into a slave in America. Slaves were either imported (until 1807, when President Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves) or were born to slave parents. The reason slavery is so associated with race in the American mind is that in the American era, Africa was the only continent left where free people were still being captured into slavery. This was being done by other Africans and to some extent in East Africa by Arabs. It was two white men, William Wilberforce and David Livingstone, who put an end to all that in the mid 19th century.